My Courses

My teaching experience includes an unusually broad range of courses. I’ve taught introductory and advanced seminars at a small liberal arts college in the US, delivered ‘supervisions’ for Cambridge undergraduates, and taught introductory lecture courses at public universities in Europe and Asia. My topics have ranged from the history of tragedy to Victorian literature and from literary theory to contemporary literature and cinema. A sampling of my courses is available below.

Tragic Drama

What constitutes a tragedy? Both “tragedy” and “tragic” have acquired a life of their own in the public discourse: we routinely use these terms to describe untimely deaths and natural disasters, plane accidents and the devastation of terrorist attacks. And while such popular references to tragedy are not without merit, in this course we will seek to give these widely used terms a more precise meaning. Where is the line that divides the tragic from the simply dreadful, and what does a tragedy demand other than the sense of enormous suffering? Over the course of the term, we will approach tragedy as a form of ethical exploration, a genre which focuses on harrowing violence and unbearable pain in order to ask difficult questions which test the very limits of moral and social order: What is the distinction between justice and revenge? What happens when individual morality clashes with the law? How to act when facing equally compelling but seemingly irreconcilable moral obligations? What is the moral responsibility of someone who is forced into wrongdoing? Some of the texts we explore include Aeschylus’ Oresteia, Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex, Euripides’ Medea, Shakespeare’s Hamlet and King Lear, as well as a host of more contemporary plays.

This course introduces students to that strange, exciting, and paradoxical period known as the Victorian Age — the time of unprecedented economic expansion, the growth of great urban centers, technological change, and scientific advancement, but also of shocking urban poverty, political unrest, and imperial expansion. In order to understand this contradictory period we will turn to such writers as Charles Dickens, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Charlotte Brontë, and Elizabeth Gaskell. We also engage a healthy dose of Victorian musings on revolutionary violence (Thomas Carlyle), gender roles (Harriett Martineau), and poverty (Friedrich Engels, Henry Mayhew, and just about everyone else).

Victorian Literature

A series of two consecutive courses intended to help first-year students master some of the basic theoretical concepts and main developments in the history of literature in English. We examine a range of concepts related to genre (tragedy, short story, lyric poetry, farce), periodization (Romanticism, Modernism, Avant-Garde), technique( deux ex machina, narrative perspective, stream of consciousness), and read texts by authors as diverse as Sophocles, Shakespeare, Wordsworth, Oscar Wilde, T.S. Eliot, Virginia Woolf, Langston Hughes, Jean Rhys, Toni Morrison, and Jhumpa Lahiri.

Introduction to Literature

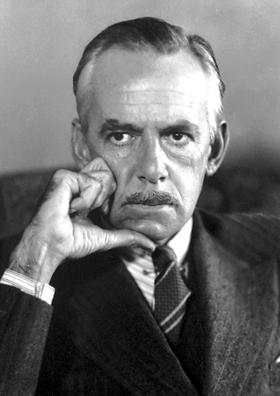

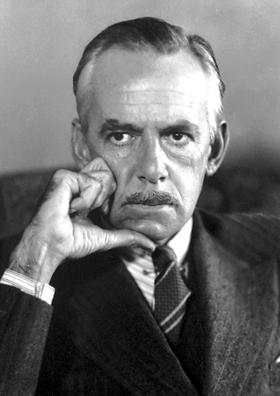

We begin at the beginning, which is to say: with Ibsen and Strindberg. We then march through a succession of great twentieth-century plays which exemplify some of the major tendencies of the century. We look at such texts as Six Characters in Search of an Author, Waiting for Godot, Long Day’s Journey into Night, and Death of a Salesman. We also look at some contemporary cinema and reflect, along with Raymond Williams and George Steiner, whether there is such a thing as modern tragedy (of course there is).

Modern Drama

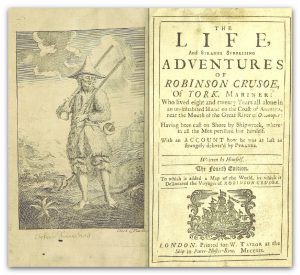

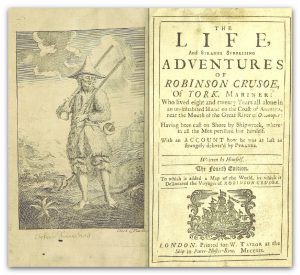

We cover as much as we can reasonably chew on. Our aim is to explore the unique variety of things that passed as ‘novels’ over the past three hundred years or so. We begin with Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (1719), an important early example of the modern novel, then move to Jane Austen’s remarkable use of romantic comedy in Pride and Prejudice (1813). With Charles Dickens A Tale of Two Cities (1859) we explore the genre of the historical novel, and with Virginia Woolf’s The Waves (1931) we move into the demanding territory of modernist fiction. We end with Ray Bradbury’s dystopian Fahrenheit 451 (1953). In the process, we examine various ideas about novelistic form (including those of Russian Formalists and French Structuralists), along with a range of important reflections on the novel’s relationship to history and society (such as those by Georg Lukacs, Mikhail Bakhtin, and Franco Moretti.

The Novel

What does it mean to become someone in a world as complex as the one we inhabit—a world defined by rapid globalization, by the legacies of colonialism, by unprecedented mass migrations? This course aims to answer such questions by exploring the creative responses to the experience of growing up and building an individual identity in contemporary fiction: focusing on stories, novels, and films, we follow young women and men struggling with conflicting cultural demands, and seeking to navigate the complexities of life in a globalized world. Works by Caryl Phillips, Nadine Gordimer, Jhumpa Lahiri, Tsitsi Dangarembga, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Hanif Kureishi, and others.

Being Someone

© 2025–2026 Aleksandar Stevic. All rights reserved.